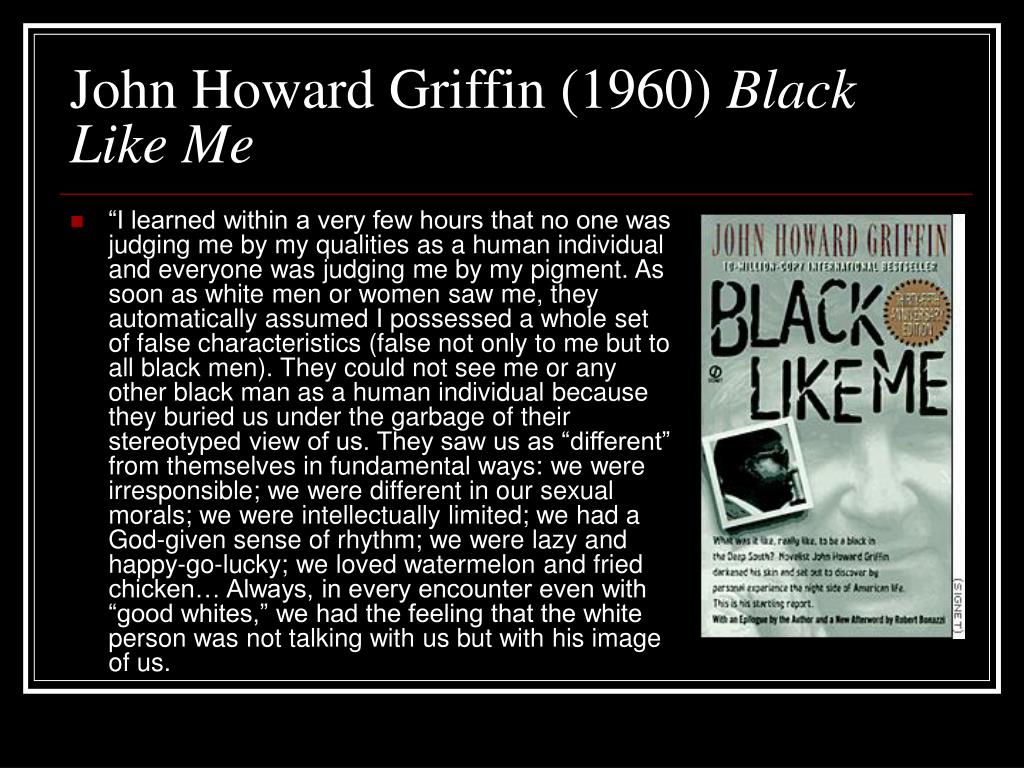

He does not become calloused to these things - the polite rebuffs when he seeks better employment hearing himself referred to as a nigger, coon, jigaboo having to bypass available rest-room facilities or eating facilities to find one specified for him. His day-to-day living is a reminder of his inferior status. All the courtesies in the world do not cover up the one vital and massive discourtesy - that the Negro is treated not even as a second-class citizen, but as a tenth-class one.

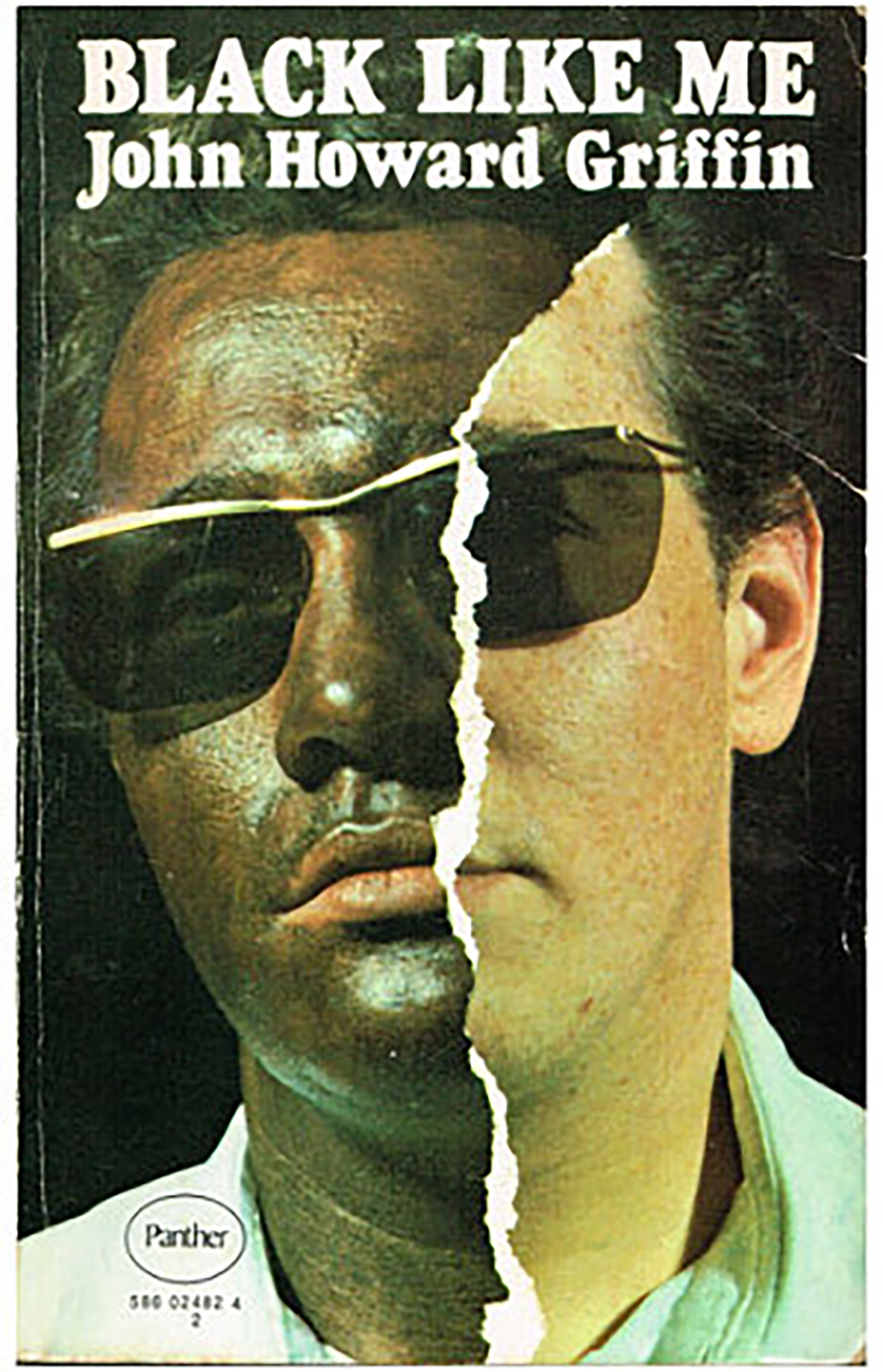

My first, vague favorable impression that it was not as bad as I had thought it would be came from courtesies of the whites toward the Negro in New Orleans. That feeling, however, didn’t last long.Īfter a week of wearying rejection, the newness had worn off. Griffin started his experiment in New Orleans, and, initially, he thought that the city’s whites were nicer to blacks than he’d expected. I felt strangely sad to leave the world of the Negro after having shared it so long - almost as though I were fleeing my share of his pain and heartache. On December 14, a little more than five weeks after he’d started, he resumed his white identity a final time. Then, for 16 days, he moved back and forth between the black and white worlds, finding ways to tinker with his coloring so that he could pass for white or pass for black as he needed. Under a doctor’s care, he took drugs to darken his skin, he laid under a sun lamp and he used dye on the most visible parts of his body: his face, arms and legs.įrom November 8 through November 28, he spent his days and nights as a black man in Louisiana (New Orleans), Mississippi (Hattiesburg and Biloxi), Alabama (Mobile and Montgomery) and Georgia (Atlanta). For twenty-one days in 1959, John Howard Griffin, a white journalist and novelist from Texas, moved through the Deep South as black man.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)